CATHERINE IN SYDNEY

Catherine Noon was listed in the shipping documents as 15 years of age (yet, amazingly, she was already 28!), unable to read or write, and suitable as a domestic. She and the rest of the girls were checked by the health authorities while still on board and then transported to the Female Immigration Depot which had been set up at Hyde Park Barracks. This was, in effect, a hostel and refuge for the young women, in charge of Mrs Capps, the Matron, who, from newspaper advertisements at the time, appears to have (also?) run a type of employment office for domestic labour out of a Registry Office at 145 King Street.

The following advertisement then appeared in the SMH of 3/8/1850 on page3:

Immigrants per Tippoo Saib - The callings of the adult immigrants per Tippoo Saib, and the number of each calling, are as follows, viz.: Males – Agricultural labourers, 13, married; policemen, 2, married; house servant, 1, married; schoolmaster, 1, married.today, between the hours of ten a.m. and four p.m., the hiring of the male immigrants will be proceeded with. The Orphans will be landed from the vessel, and lodged in the Depot at Hyde Park Barracks, where they will be prepared for entering into service in about a week.

Sentiments still ran high against these poor, homeless, defenceless girls.

Melbourne Argus 24/1/1850: “ . . . it is downright robbery to withhold our funds from decent eligible well-brought-up girls (i.e. English girls), who would make good servants today, and virtuous, intelligent wives tomorrow, and lavish them upon a set of ignorant creatures whose whole knowledge of household duty barely reaches to distinguish the inside from the outside of a potato, and whose brief employment hereto has consisted of some such intellectual occupation as occasionally trotting across a bog to fetch back a runaway pig.”

Mrs Capps had her own opinion of the girls, which she did not always keep to herself: “They require to be taught the common household duties but expect wages of good servants from England or Scotland. Thus, as long as there are English or Scottish, the Irish find it difficult to procure situations and as a consequence remain a long time at the depot.”

Poor creatures. The agents in Dublin had spread the word that women were so scarce in the colonies that gentlemen would drive down to the wharves in their carriages and carry them off to be married!

Something that we, today, tend to overlook is that these girls were, in the main, uneducated through no fault of their own, Catherine could neither read nor write, and their natural language would have been Irish Gaelic, not English! A language which they might have first been exposed to only on the voyage out.

Six years later, in 1856, Catherine, all on her own, had managed to save up the four pounds to deposit with the Government Immigration Office to arrange Martin's passage to Sydney. To put this into some kind of perspective, Catherine, if she was working for a ‘good’ household, would have been paid at the average rate, (for Irish girls) of three shillings a week (less than eight pounds a year) plus keep, out of which unscrupulous employers were wont to deduct spurious amounts for clothing and ‘toiletries’, etc.

It was a fact noted by a Select Committee on Irish Immigration held in May-June of 1858 that, as opposed to the English and Scottish, the Irish serving girls "devoted a large portion of their wages to bring out their parents, brothers, or sisters.

Masters were not only obliged to instruct their apprentices in the craft of general house servant, but to provide ‘suitable meat and drink, medicine and medical attendance when required, lodging, bedding and all other things (clothing excepted) needful and meet for an apprentice’. They were bound to pay particular attention to the moral welfare of their charges and to allow attendance at divine worship at least once every Sunday.

Under Remittance Regulations the four pounds paid for Martin's passage would ensure that, on arrival, the names of all the passengers under the off his ship would be advertised in the SMH together with a time and date for prospective employers to visit the ship. The regulations provided that if employment hadn't been offered to Martin within 10 days of arrival, then he would be obliged to leave the ship!

Sadly, of Catherine there is little further trace beyond her paying for Martin’s passage out, except for two official-looking personal advertisements in the SMH on 25th June 1864 and the Sydney Mail of 2/7/1864, attempting to contact her brother: “If Martin Noone last direction Dingo Creek, (Manning River) will write to his sister, Catherine, Post Office, Parramatta, he will oblige. Anyone sending information of him to the same address will greatly oblige.”

No record could be found that she never married, and the only further record is the death of a Kate Noon, from Ireland, on 23/6/1880 in the Hyde Park asylum, of chronic meningitis. There are good grounds for accepting that this is our Catherine as there is no other Kate or Catherine Noon(e) listed in the Irish immigration records to Sydney during the period under consideration.

It is hard to even guess at Catherine’s life in the colony.

Almost without exception, the Irish girls were married within a few years of their arrival, but an exhaustive search has not thrown up anything in her name. It is possible to deduce that the rigours and diseases of her early life left their mark and she may have been less than comely, and years of famine may have had their toll. It is very probable that she lived a life of servitude in the colony, or even resorted to prostitution as happened to many of the deemed 'unsuitable' girls, to then die a lonely death on 23/6/1880, aged 50 years, from ‘chronic meningitis’ in the Hyde Park Asylum as a ‘pauper’. Catherine’s “chronic meningitis” would most probably have been an original streptococcal infection, inadequately treated (there were no antibiotics then!). Long term complications of this disease include subdural accumulation of fluid, deafness, paralysis of certain muscles, and mental retardation. Catherine’s earlier years in Ireland would not have fortified her against such an infection.

It is quite probable that the two newspaper advertisements in 1864 were an official attempt to contact the next-of-kin of Catherine already in dire straits. The Parramatta reference is a clue to the infamous Parramatta Female Factory where, in 1861, building commenced on a new sandstone ward for the criminally insane and proceeded over a number of years with the second floor added by March 1864 and a third floor in 1869. These additions did little to improve conditions and by 1872 the institution was in a very poor state and rife with corruption perpetrated on a large scale by many of the staff.

Admission to the Asylum was by application to the Government Asylum Board or, in urgent cases, at the instigation of police magistrates. The criteria for admission were infirmity and inability to support oneself. Many of the inmates had tuberculosis (which can be a precursor to chronic meningitis) or suffered from the effects of alcoholism.

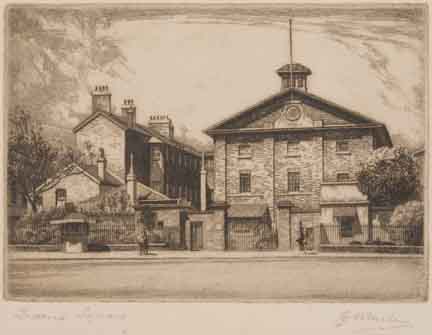

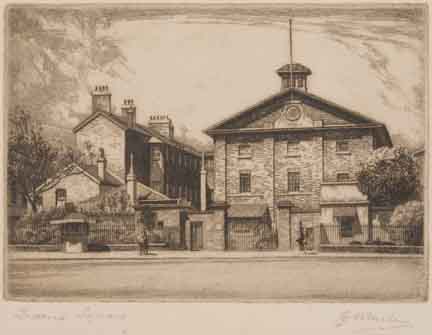

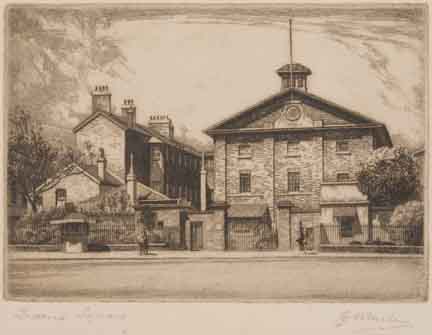

In 1862, the top floor of the Hyde Park Female Immigration Depot had been converted into an asylum for infirm and destitute women. Inmates were discharged if their health improved but many stayed for years. It is thus possible that Catherine was discharged from Parramatta and was re-admitted to Hyde Park after a later relapse, or remained at Parramatta for many years and was simply transferred to Hyde Park as her condition deteriorated.

Both asylums were less than salubrious; squalid, unhygienic, overcrowded with poor sanitation and overrun with rats which ate everything in sight. And in desperation, in 1866 the dispensary at Hyde Park was lined with galvanised iron in an effort to keep them out. There were no trained nurses and the sick were given 'medical comforts' such as grog (rum and water), milk, arrowroot, sago and sugar by the sub-matron and any able-bodied inmates. Asylum women died of many illnesses including tuberculosis, heart disease and cancer and the government report of 1882 recorded that a quarter of the inmates had died during the year. Apparently, this annual death rate was unremarkable. The women were granted day leave once a month. Alcohol was banned so on their return they were searched at the front gate in an effort to control illicit consumption, but even so, they still managed to smuggle it in and hide it under the floorboards from the watchful eye of Matron Hicks. They slept in overcrowded dormitories on iron beds using unbleached calico sheets sewn by themselves. They were fed a monotonous daily diet of half a loaf of bread, one pound of boiled beef or mutton with potatoes, turnips, or cabbage and a pint of tea. Soup was frequently on the menu and roast meat for 'special days'.

The following excerpt from the SMH of 8//6/1880 would appear to give a 'sanitised' account of conditions: “The annual treat given to the inmates of the Hyde Park Asylum took place yesterday when the old and infirm women located there were afforded the means of enjoying themselves to their hearts' content. The total number of inmates at present in the asylum is 284 – a good many of whom are verging into their 80th or 90th year; and the scrupulously clean and comfortable appearance of the various departments of the institution reflect the highest credit upon the matron, Mrs W. H. Hicks, who, by her kindly treatment and sympathy towards the inmates, proves herself I to be a true friend to the poor old creatures. Several of them have been in the institution for nearly twenty years, and notwithstanding their poverty, they all seem to be happy and contented with their lot. Yesterday's festival was got up entirely by private subscription, and the interest taken in the institution was evinced by the large number of ladies and gentlemen who were present during the afternoon. A number of the visitors took occasion to inspect the wards of the asylum, and the excellent manner in which the general arrangements of the institution are carried out evoked on all hands but one opinion as to the cleanliness of the ward. The hospital is well ventilated, and everything is done to conduce to the comfort of the sufferers. Dinner was served to the whole of the inmates in the long dining-room of the institution, where they were regaled with luxuries which they do not often get such as roast fowl or turkey, &c, and palatable pastry. His Excellency arrived shortly after 5 o'clock, accompanied by Lady Augustus Loftus; and an excellent entertainment was given in the large hall, which had been very tastefully decorated with flags and evergreens for the occasion. Several well-known artists kindly gave their services, and it was quite pleasing and gratifying to observe the expressions of delight and enjoyment with which the various items on the programme were received.”

HYDE PARK ASYLUM Having no training or previous , it is supposed she was employed as a scullery maid or laundress. A resident workforce was constantly on call, and hours of leisure were few. The banked fire in the kitchen must be revived very early in the morning to cook everyone’s breakfast, and to warm water for ablutions. In large experiencehouses a scullery maid might be first in the kitchen with cooks and other workers closely following. Male body servants, lady’s maids and nursemaids must be dressed and alert when attending their individual gentlefolk. In cooler seasons bedroom and dining room fires might be rekindled, cleared away and laid again for the evening, all in quick succession. Dust in dry seasons, and mud in wet ones, complicated the regular cleaning and strengthened and strained the backs of the working women. The feeding and cosseting of gentlefolk extended well into the evening, and could pass midnight when guests were entertained. And someone had to lock up the house after they were gone.

The classification of a job as ‘women’s work’ had little to do with the physical strength or stamina required. Female cooks, kitchen-hands and scullery maids habitually shifted large weights. Housemaids carried hot water and firewood to all levels of the house, and moved furniture and mattresses as a matter of course. Laundresses filled tubs with water from buckets, stirred or scrubbed and squeezed clothes and bedding, and carried the sodden items to hang out to dry. They then starched and ironed using heavy cast iron implements which were heated on the stove.

Through all this the dinner talk of the men centred on business, whilst that of the ladies was continual complaints about the insolence and incompetence of the serving classes. Some even lamenting loudly the passing of transportation and the loss of ‘assigned’ convict staff who, at least, could be punished for insolence.

A COLONIAL KITCHEN